Guido Harari / Contrasto Redux Guido Harari / Contrasto Redux "Better to make mistakes than be totally correct… The whole idea was to try and do something that could help produce new ideas in the future. However much we criticize art for being commercial, it is still a place for freedom and thinking and creativity." - Miuccia Prada If I were to attempt to follow my thread of musings in the art world and how they manifest in the form of this blog, the common denominator is most likely my belief in the manifest value of taking risks. Through the works and minds of such disparate characters as Olaffur Eliasson, Marcia Tucker, Alanna Heiss, Bruce Nauman, Dave Hickey, Robert Irwin, Lady Gaga, and Banksy (to name a few), I have explored the ways that taking risks -- and being uncertain of their outcome -- incites dialog, innovation, fury, passion, transformation. In the June issue of Vanity Fair, Ingrid Sischy (former Editor and Chief of Interview Magazine) reports on Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli's approach to fashion, life, and the creation of the remarkable art collection that will be presented publicly for the first time in conjunction with the Venice Biennale next month. The Prada Foundation's new home is a 65,000 square foot 18th-century plaza on the Grand Canale in Venice. Sischy describes Prada and Bertelli as collectors dedicated to risk and outside-the-box ideas in the arts, supporting extraordinarily ambitious projects, massive in scale and frequently volatile in nature. "When it comes to materials and logistics, says Prada, 'we are attracted to the nightmares.'" Prada and Bertelli are remarkable for their approach to collecting. They are unique voices amidst the predictable and often cliché accumulations of high profile art collectors. Not interested in the checklist of heavy auction hitters and the art stars of the moment, "Prada and Berletti have become legendary in the fashion and art world for making their own rules. But they are also believers in careful study; thus, when they decided in the early 1990's to focus on modern and contemporary art as collectors, and to create a foundation that would support outside-the-box ideas, theirs was a commitment." Contemporary art can create space for independent thought beyond conventional structures and tacit social boundaries. It can electrify minds and create new conduits to experience life, with its issues and conflicts. Prada and Berletti are clearly active and engaged participants in an important international art dialog that involves innovation, originality, and risk. Describing the inaugural exhibition to be presented next month, Sischy asserts that "new ideas don't come along that often, but the exhibition provides a kind of petri-dish environment in which they can cook. Or think of it as a jam session, with artworks riffing on one another thanks to evocative or provocative juxtapositions - Prada likes surprising couplings and unexpected combinations in her fashion as well as her art." Promoting the possibilities of art, what Tate Director Nicholas Serrota describes as "the nerve endings of contemporary art," requires an openness and excitement in the face of uncertainty rather than the assurance of subscribing to the costly and commercial status quo. Art critic and curator Dave Hickey stated that “if you don’t take risks, if you confirm the prescience of previous investors, you acquire no power, create no constituencies, and have no effect. So you must take risks." In the Vanity Fair interview Prada states it is "better to make mistakes than be totally correct. We want to do something alive… The whole idea was to try and do something that could help produce new ideas in the future. However much we criticize art for being commercial, it is still a place for freedom and thinking and creativity."

0 Comments

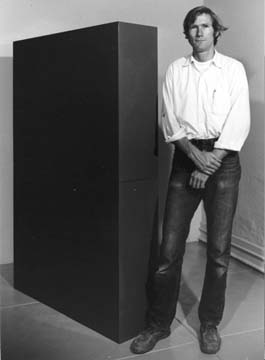

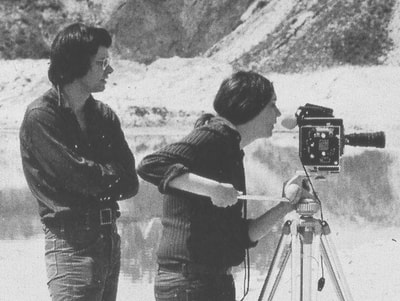

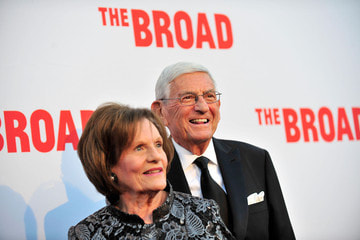

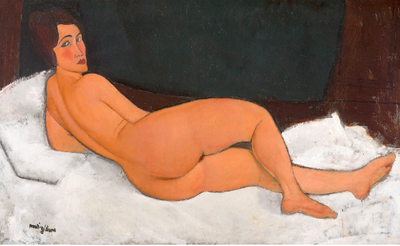

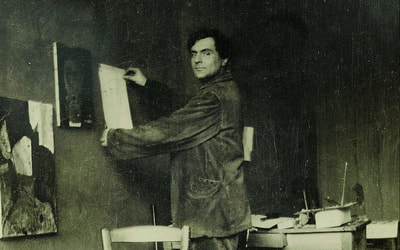

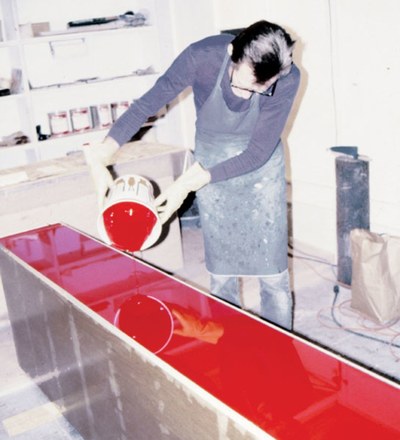

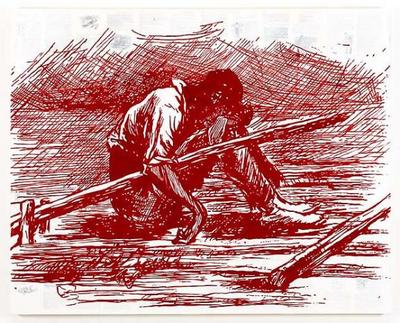

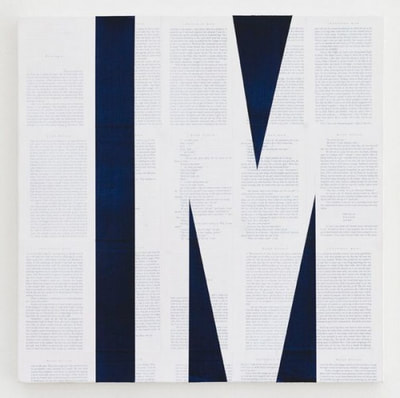

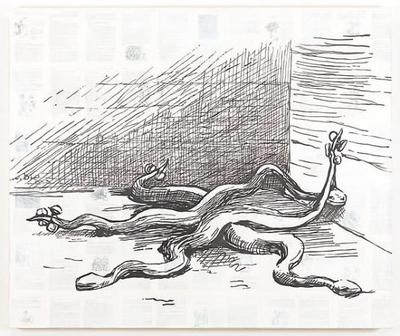

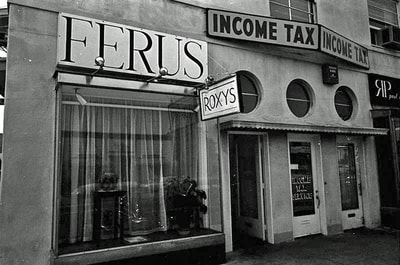

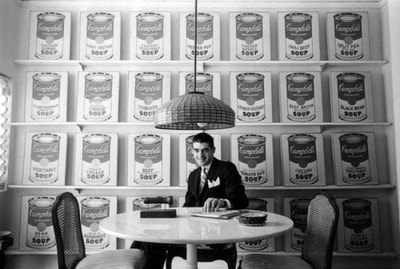

On Sunday I attended a lecture and book signing by internationally celebrated artist Nancy Holt. The event was held at the Santa Fe Art Institute for the release of her newly published book Sightlines, a comprehensive survey of photography, installation, video, film, sculpture, and land art ranging from the 1960 through today. I first met Nancy Holt several years go when she lectured at the Center for Contemporary Arts in conjunction with a Land Art exhibition I co-curated with Bill Gilbert, the Lannan Chair of Land Arts of the American West. The exhibition was a 5-year survey of the Land Arts of the American West program – a unique land art program shared by the University of New Mexico and the University of Texas, Austin (featured this month in The New York Times). I recall being drawn to Holt’s incredible history (she spent her early years as an artist in New York with colleagues and collaborators including Michael Heizer, Carl Andre, Eva Hesse, Richard Serra and Robert Smithson – to name but a few), her unassuming manner with the audience, her endless curiosity for the world around her. I had not seen Nancy in many years when I recently was invited to join her for dinner. The dinner conversation was as intriguing as her initial lecture, we meandered through topics including monumental works of land art, the process of digitalizing her image archive, the trajectory of art history, buddhist practices, Italian art hotels, her ongoing interest in reliquaries. Her lecture on Sunday followed a more focused but equally engaging and complex process of contemplation. At the lecture we learned that Sun Tunnels, arguably her most renowned work of art, was created as an installation of orientation within the awesomely vast and impersonal landscape as the Utah desert just beyond the Bonneville Salt Flats. Holt's work often brings a personal and human scale to the immensity of the landscape within which she works - a vastly different approach than, and nearly opposite to, her male Land Art counterparts. Her work represents a moment of respite and orientation to otherwise vertiginously open and enormous spaces. Holt is an alchemist of sorts, and much of her talk was about transformation – transformation of light into sculpture, sculpture into photography, photography into print, print into digital scans, digital scans into a power point presentation. She described a piece she created for an exhibition in Denver in the early 1990's. Her father had photographed a garden, and then created a painting from that a photograph. Holt photographed her father's painting, and then it was reproduced in a catalog. She then photographed the image from the catalog, and photocopied the photograph. She then faxed it to friends as an object of art that stated (something like): This is a facsimile of a photocopy of a photograph of a photograph of a painting of a photograph of a garden. She noted at the lecture that as each fax printed the image slightly differently, with varying proportions, ink output, and data markings, each person owned a slightly different iteration of that work of art. She then, chuckling to herself, looking at the image on her slideshow presentation, said she would have to add "digital scan of a slideshow presentation of a projection." Her focused fascination with the alchemy of light, time, and technology recalls the Henry Miller quote, “The moment one gives close attention to anything, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself." One perfect example - the holes that are spaced throughout the Sun Tunnels are made in the form of constellations so when the sun – a great star itself – shines through the tunnels it creates unique constellations inside the sculptures so each visitor can walk on stars. So much of what we might take for granted on a daily basis – light, time, medium, perspective, reflection, optics – is explored in Holt's art with astounding dedication and focus. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery of Columbus University described that "Holt developed a unique aesthetics of perception, which enabled visitors to her sites to engage with the landscape in new and challenging ways.” Holt turns each moment into Miller’s indescribably magnificent world in itself and in doing so reveals complex and spellbinding new worlds for her audiences - at once meticulously intricate and limitless in scope.  He who dies with wealth dies in shame. - Andrew Carnegie He who gives while he lives also knows where it goes. - Eli Broad Eli Broad is a controversial figure in the art world. An icon of "aggressive philanthropy," Broad is a Los Angeles brand, reputedly a control freak, and in the words of Frank Gehry, “a real pain in the ass.” In his 60 Minutes interview last Sunday with Morley Safer, however, one thing became abundantly clear. Eli Broad is one of a handful of philanthropists who are showing the world how to give. At 77, Broad has given away over $2 billion to charity and intends to continue giving. In the words of New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, "Eli Broad sets the standard. I think it's really being a role model for others. And they look at Eli and because of him, they get the ideas, 'I'm going to be innovative and be philanthropic and do some other things.' The leverage of Eli Broad is really quite amazing." Broad is one of the Giving Pledge members, a campaign initiated by Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates in which they ask those with the largest fortunes in the world to commit to giving away at least half their fortune during their lifetime or after their death. This dynamic philanthropic leadership has, in the words of Fortune Magazine's Doris Burke, “the potential to dramatically change the philanthropic behavior of Americans, inducing them to step up the amounts they give. With that dinner meeting, Gates and Buffett started what can be called the biggest fundraising drive in history. They'd welcome donors of any kind. But their direct target is billionaires, whom the two men wish to see greatly raise the amounts they give to charities, of any and all kinds.” Broad frequently quotes Andrew Carnegie's statement "he who dies with wealth dies in shame.” Broad then adds that “he who gives while he lives also knows where it goes.” A window into both the intention and the potential of philanthropy, Broad, Gates, Buffett, Mark Zuckerberg, Ted Turner, and a handful of other leaders are leading by powerful example. These dynamic philanthropists recognize that giving at any level is a learned behavior. To pitch the concept of The Giving Pledge, David Rockefeller Sr. hosted a dinner that included 12 of the wealthiest guests in the world. At that dinner, each was asked to tell a story of how they learned to give. In Burke's words, “David Rockefeller Sr. described learning philanthropy at the knees of his father and grandfather. Ted Turner repeated the oft-told tale of how he had made a spur-of-the-moment decision to give $1 billion to the United Nations. Some people talked about the emotional difficulty of making the leap from small giving to large. Others worried that their robust philanthropy might alienate their children. (Later, recalling the meeting, Buffett laughed that it had made him feel like a psychiatrist.)" In the 60 Minutes interview, Eli Broad emphasized that his sense of being wealthy was heightened when be began to give his money away. He realized that his money and his life mission was not to simply maintin the status quo, but to make things different and better. Culture cannot exist without altruism and in Broad’s words "civilizations are not remembered by their business people, their bankers or lawyers. They're remembered by the arts.” The reach of philanthropy extends far beyond the arts. The charitable causes that The Giving Pledge dinner guests discussed ranged from education, culture, healthcare and hospitals, public policy, and poverty. Bill Gates stated after that dinner that the event was amazing, the causes admirable, and "the diversity of American giving is part of its beauty." Support for progress that occurs at the community level has the capacity to influence policy and engender change on a national and global scale. Regardless of the size or type of contribution, it is critical to give. In Burke’s words, “society cannot help but be a beneficiary…nor will it be just the very rich who will perhaps bend their minds to what a pledge of this kind means. It could also be others with less to give but suddenly more reason to think about the rightness of what they do.”  Meryle Secrest's new biography Modigliani: A Life sheds new light on Modigliani's life-long battle with Tuberculosis. Known for his Francis Bacon-esque life of hard drinking, drugging, and womanizing; this biography posits that Modigliani's drinking and drug use was “a cover (or a compensation) for the debilitating tuberculosis that he kept secret –- a spasmodic condition managed with the opium, laudanum and alcohol that contributed mightily to his tragic death at 35.” The epidemic of Tuberculosis in Europe from 1800 - mid 1900's was a terrifying and deadly situation - one that could be likened to the AIDS epidemic of contemporary society. A contagious disease without a cure at the time, "consumptives" were frequently shunned and ostracized from society. Secrest's hypothesis is that Modigliani would have gone to any extreme to hide his condition. Immoderation, however, was also a part of the artistic lifestyle - fuel to the creative force - and the majority of artists, writers, dancers, and actors living in Paris in the early to mid 1900's lived in the extreme. Among Modigliani's great and influential peers at the time included Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Constantin Brancusi and Chaim Soutine. Each felt destined for a special fate in life, one that released them from the conventional mores and standards of their time. As Secrest describes, “like Frank Lloyd Wright a few years later, Modigliani was clearly influenced by Nietzsche’s theories about the emergence of the Übermensch. The artist, as Superman, was divinely endowed, therefore divinely inspired, for as Nietzsche also wrote, the artist had his own truth, or a special kind of truth. ‘He fights for the higher dignity and significance of man; in truth, he does not want to give the most effective presumptions of his art: the fantastic, uncertain, extreme, the sense for the symbolic… the faith in some miraculous element in the genius.’” In a letter to a friend Modigliani wrote that “People like us… have different rights, different values than do the normal, ordinary people because we have different needs which puts us – it has to be said and you must believe it – above their moral standards.” Modigliani and peers believed they were different, chosen, fated. “In his mind, fatalism and idealism, creativity and death, seemed intertwined.” The conviction that the true artist is one destined to live a tortured and extreme life beyond the bounds and rules of conventional society remains to this day. One of Bruce Nauman’s iconic works of art is a neon installation that reads “The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths.” Nauman, in describing this piece that proclaims the artist as outlier and oracle, stated that “the most difficult thing about the whole piece for me was the statement. It was a kind of test—like when you say something out loud to see if you believe it. Once written down, I could see that the statement [...] was on the one hand a totally silly idea and yet, on the other hand, I believed it. It's true and not true at the same time. It depends on how you interpret it and how seriously you take yourself. For me it's still a very strong thought.” Just add tragedy and stir.  John McCracken, a West Coast artist based in Santa Fe, New Mexico known for bright, lustrous, minimal sculptures died on Friday in New York. He was 76. I do not remember the first time I experienced John McCracken’s sculptures. It was most likely at James Kelly Contemporary in Santa Fe. I can not recall the specific colors of the works or how they were placed within the space. I do know that they haunted me for days following the show. In that rare and remarkable way that precious few works of art function, his sculpture shifted the way that I experienced anything that was even peripherally visually related. Whether it was a sumptuously painted lowrider in Northern New Mexico or a Donald Judd sculpture at Pace Gallery in New York, McCracken's sculptures changed the way I observed the world. McCracken once stated that his “tendency is to reduce or develop everything to 'single things' — things which refer to nothing outside [themselves] but which at the same time possibly refer, or relate, to everything." His work was a whisper in a cacophony of voices, and the simplicity and elegance of that intention leaves an enduring and singular impact. Artdaily.org described his sketchbooks which shed significant light on “both personal and speculative observations about the function of art. Ranging from one-word statements to several pages of commentary, his notes were frequently inspired by ancient history and paranormal meditations. These facilitate a parallel understanding of his works, as evidenced in a passage from 1966 on the reflective, even surfaces of his sculptures: “if the viewer is in motion, the sculptures become in a sense kinetic, changing more radically than one might expect. At times, certain sculptures seem to almost disappear and become illusions, so rather than describing these things as objects, it might be better to describe them as complexes of energies.” McCracken's work gave the art world elegant, minimal, infinite objects of art. In the words of a mutual Santa Fe friend, “Not only was he a great and unique artist, but he was a thoughtful, kind and subtle soul.”  I have been thinking about how the arts impact culture - considering the factors of the art world that both frustrate and inspire me - that bring me to the brink of insanity and back again, heart on fire. I recently learned of Olafur Eliasson's new art school in Berlin, The Institut für Raumexperimente. This school, and Eliasson's vision, encapsulates in so many ways the way the art world could function - by not having all the answers, but by living a life of inquiry and uncertainty. Doubt functioning as a fundamental principal of learning and innovation. Marcia Tucker, the founder of the New Museum, was fired from the Whitney for a Richard Tuttle exhibition she curated far before he gained international notoriety. The art, Tucker's unusual approach to its presentation, and a post-exhibition catalog proved to be too much for audiences to bear. When the exhibition opened, “people went berserk. People tried to pull the delicate wire pieces off the wall. They scrawled pencil comments of their own next to some of the works when the guards weren’t looking. They complained bitterly that it wasn’t art.” Audiences were offended by the inquisitive nature of the exhibition and by the fact that Tucker did not present answers, only more questions. Tucker had organized this exhibition to see what might come of the project, to learn something new, to explore new frontiers in the arts. “‘I don’t know’ is the honest answer when you’re working investigatively, but it can get you in trouble. You’re supposed to know, and if you don’t you’re going to be seen as unprofessional rather than adventurous.” Eliasson addresses this directly in the form of an art school, "to acknowledge one’s insecurity rather than progressing according to rationalised and standardised modes of understanding. By accommodating uncertainty, I think we strengthen our ability to re-negotiate our surroundings. Let me therefore suggest a principle: the success of a model lies in its ability to re-evaluate itself. It thus emerges that no artistic formula is waiting at the end of our inquiries." It is Tucker's spirit - and the mission of Eliasson's art school - that sustains my confidence in the art world. Eliasson's mission statement follows. And nothing is ever the same. Nothing is ever the same The Institut für Raumexperimente is in itself an experiment. To me, the experiment as a mode of inquiry is necessary if we are to insist on a constant, probing and generous interaction with reality. Or to put it differently: by engaging in experimentation, we can challenge the norms by which we live and thus produce reality. Due to its obsession with primarily formal questions, art education has, I believe, seriously failed to acknowledge the fact that creativity is a producer of reality. The hierarchical transmission of knowledge practised in many art schools is clearly unproductive: the inflexible categories of ‘teacher’ and ‘student’, working in a sealed-off environment, and the fundamentally unequal relation between the two, have taken responsibility away from the students, distancing them from real work in real life. But to study and to produce knowledge shouldn’t imply a withdrawal from society. There have, of course, been exceptions. Within the history of spatial research, educational experimentation has occurred at, for instance, the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, founded by Gyorgy Kepes and based on his engagement with the New Bauhaus School in Chicago; in the work of Joseph Albers and his teaching at Black Mountain College; in O.M. Ungers’ 1960s classes at the Technical University in Berlin; at the Institut des Hautes Etudes en Arts Plastiques in Paris, founded by Pontus Hultén with Daniel Buren, Serge Fauchereau, and Sarkis; and in the work of other pioneers for whom life, individual engagement, and studies could not simply be separated. I aim to recast their radical notions of learning in contemporary society. The educational alternative I hope to offer should provide tools for the creation of artistic propositions that have consequences for the world. We must embrace re-evaluation, criticism and friction. As we leave behind the representational distance cultivated by traditional art academies, a necessary and immediate relation to the world is forged. Experimentation as a method not only informs my school, but also forms the core of my artworks and my Berlin-based studio. In my understanding, an artwork is fundamentally tied to its surroundings, to the present, to society, to cultural and geographic determinants. It activates this dense texture, thereby examining the world in which we live – and by doing so, it can ultimately change the world. It also seems relevant to examine the pragmatics involved in the organisation of my studio, its randomness and roundabout ways. This reveals a structure that continuously invents the model according to which it proceeds. The practice I have developed makes me believe in my works and studio as agents in the world. And just as my works and studio participate in a continual exchange with their environment, with the times in which they exist, so too does the school. The Institut für Raumexperimente is not a discrete space; it is inseparable from its surroundings, from Berlin, from society and life in general. One might therefore call the Institute a logical consequence of my artistic practice. At Institut für Raumexperimente, time and space are considered inseparable even at a methodological level. Space cannot be externalised; it isn’t representational and nor are the experiments with which we work. To work spatially does not necessarily entail the creation of representational distance, and we can precisely avoid this distance, essentially static and unproductive, by insisting that time is a constituent of space. Or as a friend has said: space is ‘a constantly mutating simultaneity of stories-so-far’. To institute means to begin, and the school – cultivating consciousness of time – is about beginnings in space. I hope to establish a school of questions rather than of answers; of uncertainty and doubt. It is my firm belief that we can cultivate a relationship with these unstable modes of being, letting questions spawn new questions. Currently, it seems productive to acknowledge one’s insecurity rather than progressing according to rationalised and standardised modes of understanding. By accommodating uncertainty, I think we strengthen our ability to re-negotiate our surroundings. Let me therefore suggest a principle: the success of a model lies in its ability to re-evaluate itself. It thus emerges that no artistic formula is waiting at the end of our inquiries. Just as time is inseparable from space, so too is form from content. Art isn’t a formal exercise. To me, duration, space, form, intention, and individual engagement constitute a complex whole whose performative qualities we should articulate and amplify. For this reason, our experimentation with experimentation as a format for producing art and knowledge will never focus solely on either form or content. I hope the participants at Institut für Raumexperimente will see the potential in our formation of multiple, simultaneous trajectories. To some, these trajectories will appear to be slow, to others fast, and it is precisely my aim to cultivate a high level of individual reflection. Ultimately the idea is to explore the notion of the school as a process. By doing so, we can hopefully circumvent the negative mechanisms of the current-day market economy: by commodifying our thought processes, this economy insists on a linear way of engaging with our surroundings, on linearity in our understanding of process and history. Marketability, consumption, and success are everything. The seductive virtue of a stable form lies in its conclusive nature, which in turn is a criterion for success. This I find counterproductive to the friction that may allow art to exert influence in society today. To me, nothing is ever the same. Only in this way, by virtue of the experiment, can we co-produce society, making the voice of art heard. And, if it would only realise this, art has an incredible potential to evaluate the values ingrained in society. It can consolidate a non-normative platform and evoke a sense of community based on the fact that we are all different from one another. To define community in this way is the real challenge today. The type of programme that we are trying to create at Institut für Raumexperimente is an unfolding macroscopic model of an aesthetic and social encounter. The life of the school will be dialogical, a multiplicity of voices. I hope the school participants – ‘teachers’ and ‘students’ alike – will enter the cacophony of voices that constitute its core. Giving and taking is equally distributed. Inspiration is for all. What we will produce in this encounter is reality. It will be a laboratory for experience, but probably nobody will see this experiment as being essentially a model until tomorrow. Institut für Raumexperimente is an entirely public school, realised in collaboration with the Universität der Künste in Berlin. It is not an avant-garde school model in the classical sense, seeking a blind rupture with all previous systems, nor is it a private career-oriented educational scheme. Rather, we are supporters of slow revolutions. If crucial changes happen at a microscopic level, an entire society or worldview may in time be changed. And if our school experimentation succeeds, we will be able to sustain a non-dogmatic self-criticality as part of our everyday lives. - Olafur Eliasson *Marcia Tucker quotes from her autobiography, "A Short Life of Trouble: Forty Years in the New York Art World".  L7m in Vannes, France. L7m in Vannes, France. I was asked by Kindle Project to participate in a dialog on Street Art versus Museums. The following is that conversation as it was published. The Kindle blog closes this season’s Art theme with a conversation between some great minds and artists. For us, dialogue is at the heart of how we explore what it is we do. Most of us working at Kindle Project are artists in some form or another outside of our work. Over wine, caffeine, sleepless nights, and under porches, we have spent years building art theories and breaking them down. We’ve stenciled sidewalks and shown in galleries. We’ve been inspired by JR, Princess Hijab, and dreamed of walking the streets of Valparaiso, Chile. We’ve been impressed at MOMA and wowed by Launchprojects. Recently, we’ve been asking questions about accessibility to art, the tension/cohesion between institutionalized art and street art. To help further this dialogue, we’ve solicited insight from four very diverse individuals in the art world to give us their candid reflections on a series of questions based on the broad debate of Street Art versus Institutionalized Art. We are pleased to present to you the perspectives of Cyndi Conn – Founder of Launchprojects, Pablo Acona – artist, Yozo Suzuki – artist, and Liza Mauer – founding member of Partners in Art. A special thanks to all of you. Help keep the conversation moving and share your perspective with us. Do you think that street art has a place in the context of modern art? Yozo – I am certain that street art has its place in art. From cave painting to the digital displays of the Sony building on Ginza street in Tokyo artists have been showing art on the street and in public arenas since the earliest evidence of art itself. Of course such familiar names like Basquiat, Haring, Banksy and Fairey have had very successful careers indoors as well as out. Liza – Street Art absolutely belongs in the world of contemporary art. It is an honest reflection of what is happening at a most basic grassroots level. If anything Street art holds an important entry level place for youth and a younger generation of artists. Have you seen the Banksy film, Exit through the Gift Shop? Every person I know under the age of 25 was transfixed by the film and related to its energy. I know young artists who are making street art today after learning about Banksy. Artists operate in many mediums and arenas. Street art is just one place to show and make art. Also, there isn’t much of a difference between the mass market production of Bansky, Shephard Ferry and Andy Warhol. They are all responding to mass culture. LA MOCCA is currently showing the first NA large scale show of graffiti art. Pablo – For many years I did not think street/graffiti art had a place in the modern art world because of the fact that is inherently a rebel culture that defied structure within that scene. It’s hard to argue these days that it doesn’t. Even back in the early NYC downtown art scene it had a place. The only difference is now it has become recognized as a tried and true profitable form of art so its blown up and everybody is doing it and can get a share of the market. Back in the day you had to prove yourself in the streets first, today you don’t. I think graffiti/street art always could be considered an art form it just didn’t always fit into the art world because it was made for the streets. That is where it was meant to be seen and that is where it made the biggest impression on the viewer. Now graffiti/street art is so watered down that it really doesn’t matter and most people that create it are thinking about galleries, museums and books anyway. Cyndi – Absolutely. Street art is and always has been a critical voice reflecting the reality of our times, not simply pandering to the demands and whims of an increasingly rarified art market. Street art also incorporates disparate facets of society that are not always addressed in traditional art making – music, film, politics, design, fashion, language – that creates an incredible synergy. It can be the impetus for and foreshadow movements to come in the larger art and cultural market. What is the role of street art in molding public perceptions? Yozo – On the most basic level street art exposes people of all social strata to personal and political expressions. The strong tradition of social commentary in street art coupled with the freedom of showing outside of commercial venues allows for an unvarnished view point to come forward in a mainstream way. Liza – Street art generates a dialogue. It introduces a whole different constituent base to art. Art can be everywhere. It’s our era’s equivalent of the Arte Povera movement of the 1960′s in Italy. Pablo – In its purest form it is still catered to shocking and amazing the public and challenging peoples pre-conceptions of what art can or can’t be. Sparking debate, emotions and perceptions. However the form I see it in most often nowadays is in the role of commercial art. It has molded people’s perceptions as to what can be profitable and commercial. Cyndi – As i mentioned in the last question, street art can reflect the social pulse as it is transforming and becoming a larger movement or issue. Street art has both the benefit and detriment of anonymity, which gives the artist the capacity for absolute candor. I think the anonymity can be an important factor in reflecting the truth of our times. The flip side, the side that most who oppose street art would point to, is that anonymity also gives lesser minds with a spray can and time an opportunity to vandalize and debase public venues. As Nick Douglas of MOCA-latte describes the recent incident at LA MOCA, “The incident piqued my interest, not due to the issue of censorship, or the removal of Blu’s work, but the existence of a newly engaged public talking about art in Los Angeles. Deitch and his actions served as a lightening rod for debate regarding the role of the museum and art. It was exciting to see this level of discussion about art in Los Angeles – a pretty rare occurrence in this city.” Street art begins conversations. That is always a critical function of the arts. What is the role of institutionalized art in molding public perceptions? Yozo – Art institutions tend to function as a type of sieve. Whether its in a museum whose goal is to present art historical content in the context of timelines and traditions or contemporary museums and galleries who distill contemporary art through the eyes of a curator, institutions of art tend to present a selective version of the art world. Liza – Most people see art only in traditional art institutions-galleries, museums, public spaces. Institutions are critical to maintaining a cultural life in a city. Even a great street artist would be feel honoured to have an art show in a museum space. I dare them to argue the opposite. Pablo – I don’t really have an opinion on this.I almost feel institutionalized art is more authentic then most graffiti/street art these days. You go to school and you learn and develop a skill within a system. It can be limiting but that is what graffiti/street art was there for. It was an outlet from that side of art. Graffiti also was a system that artists used to work, learn, paid dues and developed in. It had rules and values that have been lost in newer generations. I think institutionalized art molds peoples perceptions as to what is viable as modern art in a classic sense. Cyndi – I like the expression of institutionalized art. I am picturing little paintings in straight jackets in white padded cells. Art housed in institutions such as museums functions to demonstrate important works of art and fundamentally why art matters. Ideally, art opens minds, reminds of past mistakes and accomplishments, encourages us to continue pushing boundaries and taking daring risks for the sake of betting our community, country, world. Does street art have a responsibility in education or informing the public? If so, what is that responsibility? Yozo – I don’t believe that artists have a responsibility to educate the public. One of the great things about art is that it can function as inspiration for thought; however, placing a burden on artists to serve any societal role negates its greatest strength. Liza – No, it has no responsibility at all. It is art!! Art for Arts sake! Pablo – Within education I think it can play an important role in teaching younger generations alternative ideas and techniques to approaching creativity and art. It also has a responsibility to teach the history of this form of art which will keep it in a context that separates it from other art. Right now the lines are blurry and there is not much difference between modern commercial art and graffiti/street art. The history is what really separates it and makes it special. Yet on the other hand street/graffiti art really has no responsibility to the public. In its purest form it is a creative backlash at the system and society that it was born and escaped from. Its anti-responsibility, anti-establishment and if its done correctly it can’t be labeled. Maybe vandalism fits. Cyndi – I think by its very nature the genre of street art should not have a responsibility in educating or informing the public. “Street Art” is a genre of radically diverse individuals with a wide-ranging intentions. I think that if street artists should be held accountable to anyone or anything that accountability should be dictated within their own system. Does institutionalized art have a responsibility in educating or informing the public? If so, what is this responsibility? Yozo – I wouldn’t call it a responsibility. Having said that, I do appreciate seeing the greatest works of art through history even as determined by a consensus of so-called art experts. I guess if one is going to stand up and say “this is great art,” then that person creates their own obligation to champion and preserve that art. Liza – Yes, it does because institutions receive funding from the government and other arts organizations so are responsible for exposing, educating and supporting the arts. If we don’t support the cultural life of our city through funding the arts, Toronto (and every other city for that matter) will be a wasteland. Art institutions primary responsibility is to expose and educate. Art shows, panel discussions, lectures, films all enrich our lives. We’d be no where without our cultural institutions. Pablo – I think institutionalized art has a similar responsibility. To educate about history, techniques and movements. Unfortunately support for art is diminishing within the educational system. This leads to the lack of unique and creative thinking and inspiration that exists today. Cyndi – It does because it is so defined. I feel the greater question is if institutions are currently doing their duty and fulfilling their responsibility in educating and / or informing the public, and how that might or could be changed to a changing public with changing needs in relation to arts and culture.  I returned last night from New York. I had mapped out everything I wanted to see - Lynda Benglis & George Condo at the New Museum, Tara Donovan and Donald Judd at Pace, Yayoi Kusama at Robert Miller Gallery, Kate Shepherd at Galerie LeLong, Anish Kapoor at Barbara Gladstone, and on and on. Along the way I stumbled without itinerary into Lehmann Maupin and was captivated by an exhibition of works by Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (Kids of Survival). Tim Rollins and K.O.S. began working together in the early 1980's when Rollins created a strategy for his students from Intermediate School 52 in the South Bronx that combined lessons in reading and writing with making art. Rollins told his students on that first day, "Today we are going to make art, but we are also going to make history." As described on the ICA Philadelphia website: In a process they call "jammin," Rollins or one of the students reads aloud from the selected text while the other members draw and relate the stories to their own experiences. These drawings are then cut and pasted or enlarged and recreated on the grid. The collaboration between Rollins and his students soon outgrew the classroom. Frustrated with the strictures of the public school system, Rollins opened the Art and Knowledge Workshop, an after-school program in an abandoned school building five blocks from IS52. After teaching all day at IS52, Rollins would meet K.O.S. members at the workshop; homework would be done and art would be made. In 1987, Rollins and K.O.S. began using a traveling workshop format to spread the ideas and inspiration behind their project beyond the South Bronx. In 1994, Rollins and K.O.S. moved their operation to a studio in Chelsea. There Rollins and some long-term K.O.S. members rebuilt and expanded the project nationally and internationally, significantly increasing the number of workshops conducted with other schools and arts institutions. Today there are active K.O.S. members in Philadelphia, Memphis, San Francisco, Seattle, and New York. Rollins and K.O.S.'s decision to exhibit the art that they had created in their classroom in professional galleries marked an important turning point in their history; it signaled the moment they began to distinguish themselves from other teacher-student collaborations and demanded that their work be engaged first as fine art. The images at Lehmann Maupin are wholly compelling, even without the back story. The majority of the exhibition consisted of elegant large-scale figurative paintings in indigos, blacks, and reds rendered in a Raymon-Pettibon-meets-Kara-Walker stroke atop white-washed pages from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby. On a far wall hung quieter paintings made from sheets from the original operatic score of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny wrapped nets of butcher's twine and gold paint. In an interview for Deutsche Bank Artmag, K.O.S. is described as "filling the gap between performance art, installation, graffiti, and Neo-Expressionism," and Rollins as "attracted to the idea of an intellectual revolution and learning. After twenty-six years, Tim Rollins is still riding that line between art, education, and a rescue operation." The exhibition continues the artists’ endeavor to challenge standard notions of art through education, collaboration, and deep engagement with literary and historical texts. The show stands alone in Chelsea in my mind for its content and intention. Again, in the words of Tim Rollins, "today we are going to make art, but we are also going to make history."  Art in its most authentic form can manifest spontaneously. Seemingly out of nowhere and with a galvanizing effect on contemporary culture, the case at hand occurred on a Staten Island Ferry with a formally ballet-dancer-gone-rogue. The New York Times Magazine featured an article yesterday on Anne Marsen, an early 20-something dancer who grew up in a competitive ballet school in New Jersey. As described by Paul Tough of the New York Times, Anne was still recovering from a high-anxiety childhood and "the ever-accelerating pressure to be the best and skinniest and en pointe-iest girl in class. Since dropping out of the University of the Arts in Philadelphia a year earlier, she had gone rogue, dance-wise, taking three or four classes a day from studios all over New York City — jazz, modern, tap, salsa, flamenco, belly-dancing, break- dancing, West African, pole dancing, capoeira — borrowing gestures and movements and boiling them all down into her own unique B-girl bouillabaisse." Her world collided with that of Jason Krupnick, who was hired to create a promotional video with dancers for footware. He posted an ad for dancers on Craigslist in exchange for slices of pizza. He was enthralled with her unique moves, used her in that video, and and six months later called her to collaborate again for a video for D.J. Girl Talk's latest album All Day, "a stew of samples lifted from 373 songs and recombined into a chaotic, propulsive mix. As Krupnick listened to the album, it struck him that Girl Talk makes music the way Anne Marsen makes dance." Marsen danced for 71 minutes, completely improvised. She is brilliant and hysterical and "weird and joyous, popping with youth and energy. At first, Marsen looks more like an enthusiastic and slightly dorky amateur than a trained dance pro. She wears regular tennis shoes and worn gray cords and an oversize, multicolored jacket, and at one point she falls off the railing of an escalator. It’s not until a minute or so in, as she twirls and gyrates through the ferry’s upper level, staring down the camera with a sly smile on her face as sleepy commuters pretend not to notice, that you start to suspect that you’re watching something more than a little magical." Anne and Jason are enjoying their viral celebrity status with their shared talents and their pure joy for what they do. An undeniable work of performance art, Anne is raw and talented and a thrill to watch. Even when she falls off the escalator. With that I will leave the words to the New York Times and the moves to Anne. Enjoy! GIRL TALK // ALL DAY HUMAN AFTER ALL all images: by Jason Krupnick, NYT  Last week I had the remarkable opportunity to have dinner with Irving Blum, Internationally renown art dealer and the force behind Los Angeles' legendary Ferus Gallery, Blum was a pioneer in the promotion of the post-war artists of the 1960's on both coasts - discovering and championing artists such asAndy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Roy Lichtenstein, Larry Bell, Ken Price, Robert Irwin, Ed Kienholz, Donald Judd, Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. I decided to watch the documentary The Cool School to learn more about the Ferus Gallery and Blum's tremendous impact both in Los Angeles and New York at that time. The Cool School uncovers and interviews virtually all of the artists, friends, collectors, and minds behind Ferus to explore how this short-lived gallery forever transformed the Los Angeles art scene. As the documentary describes, "the gallery managed to do for art in Los Angeles what the museums previously could not. Even though their modalities were as disparate as assemblage art, abstract expressionism and Pop, Ferus artists shared ideas, goals, workspaces and a lasting vision." The concepts and motivation behind both the success and closure of Ferus is further described by Blum in a 1977 interview with Paul Cummings. Blum describes that even with the excitement and rush of Ferus' exhibitions and openings, "there just wasn’t a heck of a lot of activity. There wasn’t a lot of movement, there really wasn’t. And the awful thing about selling out there, especially at the beginning, was that there was simply no pressure. So if somebody said, well, if you told somebody the price of a painting, they would say to you, “Fine, all right, let me think about it.” You’d say, “All right.” And they would think about it for a month, or two, or three and be relatively sure that when they came back into the gallery, that thing would still be there... And virtually every time out, it was still there. So they could take as much time as they liked to consider buying whatever it was they had in their head to do. Whereas in New York, if you see something and it’s really terrific, and if you say to the dealer, “Well, let me think about it,” the dealer will generally say, “Well, certainly, take 48 hours. I have other interests, I have other people coming in to look.” And you know that that’s true. In California, it simply wasn’t true. I couldn’t say, “Look, I can only give you 24 hours.” They would laugh! They would say, “Who else would buy that, for God’s sake?” And you couldn’t answer. And they’d be right, you know". When Cummings questioned Blum what he had learned over decades of dealing emerging and established art on both coasts, Blum responded that "if I knew then what I know now, I probably would have had other thoughts about doing the gallery business. I probably would have gone ahead and done it in any case, but at least I would have had a sounder base from which to operate. I would have known that it would have taken me six or seven years just to get even for example. That was something I had no idea of at the very beginning. And I would have understood that showing younger people or unknown people takes forever and is largely a thankless, difficult, expensive matter." Our conversation followed the thread of both the documentary and the interview. Blum's energy and enthusiasm for the art world continues to be contagious, his charm exhilarating. Transformation, passion, and honest examination of time and place is clearly a foundation to sustained growth and continued relevance in this capricious and mercurial world of art. |

art in lifeThe world as I experience it - through people, exhibitions, books, talks, + random happenings that lead back to art. One way or another. Archives

April 2011

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed